In the annals of dental history, few names resonate with the same gravitas as Greene Vardiman Black. Often hailed as one of the principal founders of modern dentistry, his work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries laid a foundational bedrock upon which much of contemporary dental practice is built. To understand his impact is to journey back to a time when dentistry was transitioning from a somewhat rudimentary craft to a scientifically grounded profession, and Black was a key navigator on that voyage.

A Self-Forged Path to Dental Eminence

Born on August 3, 1836, near Winchester, Illinois, Greene Vardiman Black’s early life didn’t immediately point towards a career that would revolutionize oral healthcare. He grew up on a farm, and his formal schooling was limited. However, Black possessed an insatiable curiosity and a remarkable aptitude for self-study. He was an avid reader, deeply interested in the natural sciences. This inherent desire to understand the world around him, coupled with a keen observational skill, would become hallmarks of his later scientific endeavors. His initial foray into medicine was under the tutelage of his brother, Dr. Thomas G. Black, a medical physician. This exposure likely ignited his interest in healthcare. Subsequently, he spent a few months in the office of Dr. J.C. Speer, a practicing dentist, in 1857. In an era where dental education was often an apprenticeship, this brief period was his primary formal dental training before he began his own practice.

It’s crucial to appreciate the state of dentistry at that time. Procedures were often crude, understanding of dental diseases was minimal, and materials used for restorations were unpredictable. There was little standardization, and what one dentist practiced might be vastly different from another, even in the same town. Black recognized these deficiencies early on and dedicated his life to bringing scientific rigor and systematic order to the field.

Pioneering Contributions that Shaped Modern Dentistry

G.V. Black’s contributions were multifaceted, touching nearly every aspect of operative dentistry. He wasn’t just a practitioner; he was a relentless researcher, an inventor, an educator, and a prolific writer.

Systematizing Cavity Preparation: The Dawn of “Extension for Prevention”

Perhaps Black’s most enduring legacy is his systematic approach to cavity preparation. Before his work, preparing a tooth for a filling was often a haphazard affair. Black meticulously studied the patterns of dental caries (tooth decay) and developed principles for preparing cavities that aimed not only to remove existing decay but also to prevent its recurrence. This led to his famous, and sometimes debated, concept of “extension for prevention.” The idea was to extend the cavity preparation to include adjacent tooth surfaces or grooves that were deemed susceptible to future decay, even if they weren’t currently carious. While modern dentistry, with its emphasis on minimal intervention and advanced adhesive materials, has evolved beyond a strict interpretation of this rule, its underlying principle of thoroughness and understanding caries progression was revolutionary for its time.

He outlined specific steps and forms for cavity preparation, including:

- Outline form: The shape of the cavity on the tooth surface.

- Resistance form: Features that help the tooth and restoration withstand chewing forces.

- Retention form: Features that prevent the filling from being dislodged.

- Convenience form: Modifications to allow adequate access for instrumentation.

- Removal of carious dentin: Ensuring all infected tooth structure is eliminated.

- Finishing of enamel walls: Creating smooth, strong margins.

- Cleansing of the cavity: Preparing the cavity for the restorative material.

These principles brought a much-needed order and predictability to restorative procedures, significantly improving the longevity and success of dental fillings.

Perfecting Dental Amalgam: The Science of Fillings

Dental amalgam, a mixture of mercury with a metal alloy, had been in use before Black’s time, but its properties were inconsistent and often unsatisfactory. Early amalgams exhibited significant expansion or contraction upon setting, leading to failed restorations, tooth fractures, or recurrent decay. Black undertook extensive research into the metallurgy of dental amalgam. He experimented with various compositions of silver, tin, copper, and zinc, meticulously studying their physical properties, such as setting expansion, contraction, flow, and strength. His work led to the development of a “balanced” amalgam formula, which had more predictable and stable behavior. He determined optimal alloy compositions and methods for mixing and condensing the material. His 1895 formula for amalgam (approximately 68% silver, with tin, copper, and zinc) became the standard for many decades and drastically improved the quality of amalgam restorations, making them a reliable and durable option for patients.

Greene Vardiman Black’s rigorous scientific methodology transformed key aspects of dental care. His systematic approach to cavity preparation, famously summarized by the principle “extension for prevention,” aimed to enhance the durability of restorations by addressing areas prone to future decay. Furthermore, his meticulous research into dental amalgam led to a scientifically balanced formula that significantly improved the reliability and longevity of these common fillings, setting a standard for much of the 20th century.

Bringing Order to Chaos: Classification and Nomenclature

To study and teach effectively, a common language is essential. Dentistry in the 19th century lacked a standardized nomenclature and a systematic way to classify dental caries. G.V. Black addressed this by developing a classification system for carious lesions based on their location on the tooth surface. Black’s Classification of Caries, which groups lesions into classes (originally Class I through Class V, with Class VI added later by others), is still taught and used by dentists worldwide today. It provided a simple yet effective way to describe, diagnose, and plan treatment for different types of cavities.

- Class I: Caries in pits and fissures on the occlusal, buccal, and lingual surfaces of molars and premolars, and lingual of anterior teeth.

- Class II: Caries on the proximal (mesial or distal) surfaces of premolars and molars.

- Class III: Caries on the proximal surfaces of incisors and canines that do not involve the incisal angle.

- Class IV: Caries on the proximal surfaces of incisors and canines that do involve the incisal angle.

- Class V: Caries on the gingival third of the facial or lingual surfaces of any tooth.

This classification was a monumental step in standardizing dental records, communication among professionals, and dental education.

The Prolific Educator and Author

Black was not content to merely discover; he was passionate about disseminating knowledge. He became a highly influential dental educator, serving as a professor and later as Dean of Northwestern University Dental School from 1897 until his death in 1915. Under his leadership, Northwestern became one of the premier dental schools in the world. He was a demanding but inspiring teacher, emphasizing scientific principles and meticulous technique.

His literary contributions were equally significant. He authored numerous articles and several comprehensive textbooks. His two-volume work, “Operative Dentistry” (first published in 1908), became the definitive text on the subject for generations of dental students and practitioners. It meticulously detailed his principles of cavity preparation, his research on dental materials, and his understanding of dental pathology. Another key work was “Dental Anatomy.” These texts codified much of his research and philosophy, spreading his influence far beyond those he personally taught.

Early Insights into Dental Plaque

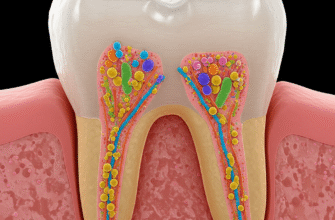

While the full understanding of the microbial nature of dental diseases came later, Black made significant early observations on the role of what he termed “gelatinous microbial plaques” (now known as dental biofilm or plaque) in the initiation of dental caries. He recognized that these films adhered to teeth and played a crucial role in the decay process, highlighting the importance of oral hygiene long before it was widely emphasized with modern understanding.

An Enduring Legacy: The Father of Modern Dentistry

Greene Vardiman Black passed away on August 31, 1915, but his influence on dentistry remains profound. He is often referred to as the “Father of Modern Dentistry” or one of its primary architects, and for good reason. His insistence on a scientific basis for dental procedures, his standardization of techniques and nomenclature, and his dedication to education helped elevate dentistry from a trade to a respected health profession. He demonstrated that dental problems could be studied systematically and that treatments could be based on sound biological and mechanical principles.

While some specific aspects of his teachings, like the aggressive “extension for prevention,” have been modified by advances in materials science (e.g., adhesive dentistry) and a more conservative treatment philosophy (minimally invasive dentistry), the core principles of understanding tooth anatomy, caries progression, material properties, and meticulous execution that he championed are timeless. His methodical approach to research and problem-solving set a precedent for future generations of dental scientists and clinicians. The instruments he designed, the classification systems he developed, and the fundamental concepts he introduced continue to echo in dental offices and educational institutions around the globe. His story is a testament to the power of dedication, rigorous inquiry, and the profound impact one individual can have on an entire field of human endeavor.