Imagine your mouth as a bustling workshop, each tooth a specialized tool. Right at the entrance, holding the most prominent position, are the incisors. These are the teeth you reveal first in a smile, the ones that take the initial, decisive action when you encounter a crisp apple or a chewy piece of bread. They are, quite literally, the front line of biting, the sharp vanguard of your dental toolkit, diligently performing their duties day in and day out.

Often described as chisel-shaped or like tiny, sharp spades, incisors are designed with a singular primary purpose: to cut. Unlike the rugged, mountainous molars at the back, built for grinding, incisors possess a relatively thin, flat edge. This edge allows them to slice through food items with precision, initiating the entire process of breaking down food for digestion. Think of them as the culinary scissors of your anatomy, snipping off manageable portions before the heavier machinery further back in the oral cavity takes over the task of mashing and grinding.

The Structure of a Cutting Edge

Humans are typically equipped with a total of eight incisors, neatly arranged with four in the upper jaw (maxilla) and four in the lower jaw (mandible). These aren’t just a uniform row; they have their own individual identities and subtle variations. We distinguish between central incisors and lateral incisors. The central incisors are the two front-most teeth in each jaw, located right in the middle, forming the very center of your smile. Flanking these, one on each side, are the lateral incisors. Generally, the maxillary (upper) central incisors are the largest and most prominent of all the incisors, giving them a starring role in your smile’s appearance and overall facial aesthetics.

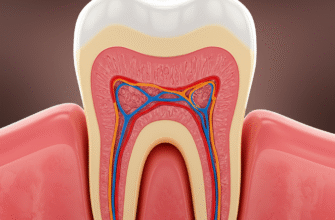

Each incisor, like any other tooth, has a visible part called the crown and a part embedded within the jawbone called the root. The crown is coated in enamel, the hardest substance in the human body, providing the necessary strength and resilience for biting into a variety of textures. Beneath the enamel lies dentin, a slightly softer, yellowish material that forms the bulk of the tooth structure and provides support to the enamel. At the very core is the pulp, a soft tissue chamber containing nerves and blood vessels, which keeps the tooth alive, responsive, and nourished. The roots of incisors are typically single and somewhat conical or slightly flattened, designed to provide a stable anchor for the forces exerted during the cutting and tearing motions of biting.

In humans, the four upper incisors are typically larger than the four lower incisors. The central incisors, both upper and lower, are generally wider than their lateral counterparts. This specific arrangement and graduation in size contribute significantly to the efficiency of the initial bite. These teeth are primarily designed for slicing and incising, not for grinding or heavy chewing, functions reserved for teeth further back.

The particular shape of the incisor crown, broad and thin at the biting edge, is perfectly suited for its function. This edge, known as the incisal edge, is what makes contact with food, initiating the cut. The slight curve of the dental arch ensures that the incisors meet in an efficient manner, often with the upper incisors slightly overlapping the lower ones, creating a shearing action much like that of a pair of quality shears.

More Than Just a Bite: The Versatility of Incisors

The primary function of incisors is undeniably biting and cutting. When you take a bite, your lower jaw moves upwards and slightly forwards, bringing the sharp edges of your lower incisors into contact with, or just behind, the edges of your upper incisors. This action, similar to how scissor blades meet, creates a shearing force that neatly severs a piece of food. The thinness of their biting edge concentrates force, allowing them to penetrate food items like fruits, vegetables, and softer meats with relative ease. It’s a beautifully efficient piece of natural engineering, honed by millennia of evolution.

However, the role of incisors extends beyond mere food processing. They play a surprisingly crucial part in speech and articulation. Try saying words with “th” (as in “think”), “f” (as in “fish”), or “v” (as in “vase”) sounds. You’ll notice your tongue or lower lip making contact with or coming very close to your upper incisors. The precise placement and shape of these teeth help modulate airflow from the lungs and create the distinct consonant sounds that form the building blocks of spoken language. Without them, or if their alignment is significantly altered, clear articulation of many common sounds would become a significant challenge, impacting communication.

And, of course, there’s the significant aesthetic contribution. Incisors are the most visible teeth in the mouth, forming the centerpiece of a smile. Their shape, color, alignment, and the way they relate to the lips and face significantly influence facial aesthetics and how we perceive attractiveness and even friendliness. A bright, well-aligned set of incisors can light up a face, underscoring their profound social importance in human interaction. They are a key feature in expressing emotions, from a joyful laugh to a thoughtful frown.

A Glimpse into Nature’s Dental Designs

The design and function of incisors are wonderfully adapted across the animal kingdom, reflecting diverse diets and lifestyles. Observing these variations provides a broader appreciation for this dental marvel. For instance, herbivores often showcase highly specialized incisors. Think of rodents like beavers, rats, and squirrels; their incisors are famous for being ever-growing. This continuous growth is essential because they are constantly gnawing on hard materials like wood, seeds, or nuts, which wears down their teeth rapidly. The enamel is typically present only on the front (labial) surface, while the softer dentin behind wears away more quickly. This differential wear creates a perpetually self-sharpening chisel edge, perfect for their dietary needs.

Grazing animals like horses and cattle also have prominent incisors. Horses have both upper and lower incisors used to clip grasses and other vegetation efficiently. Cattle, on the other hand, famously lack upper incisors, possessing a tough dental pad instead. Their lower incisors press against this pad to tear off plant matter. The way these teeth meet and shear plant material is critical for their sustenance and initial food processing.

In contrast, many carnivores, like cats and dogs, have incisors that are generally smaller and less prominent than their formidable canines, which are designed for gripping and tearing flesh. While canines do the heavy lifting, the incisors in these animals might be used for more delicate tasks such as nibbling small pieces of meat off bones, precise gripping, or for grooming, meticulously combing through their fur to remove debris or parasites. Omnivores, such as humans and bears, possess incisors that are more generalized – sharp enough to cut plant material and softer meats, but not overly specialized for one particular food source, reflecting their versatile mixed diet.

The Journey of an Incisor: From Bud to Bite

Our relationship with incisors begins remarkably early in life, even before birth, as tooth buds start forming within the developing jaw. The first set to appear in the mouth are the primary incisors, often affectionately called baby teeth or milk teeth. These usually start to erupt through the gums around six to ten months of age, with the lower central incisors typically being the first pioneers, heralding the arrival of a toothy grin. These early arrivals are crucial for a child’s ability to start chewing softer foods, for proper jaw development, and for speech development. By the age of about two and a half to three years, all eight primary incisors (four upper, four lower) are generally in place, ready to help a toddler explore new textures and tastes.

But these early arrivals are not permanent fixtures. They serve as essential placeholders, maintaining space and guiding the development and eruption path of their successors. Between the ages of six and eight, a significant dental transition occurs: the primary incisors begin to loosen and fall out, one by one, making way for the permanent incisors. Again, the lower central incisors are often the first permanent teeth to erupt, typically around age six or seven, followed by the upper centrals, and then the lateral incisors in both jaws. When permanent incisors first emerge, they often have a slightly bumpy or scalloped biting edge, features known as mamelons. These are remnants of the developmental lobes from which the tooth formed and usually wear down over time with normal use, resulting in a straighter, smoother incisal edge.

A Lifetime of Service Ahead

Once the permanent incisors are fully erupted, usually by around age eight or nine, they are intended to last a lifetime, performing their vital functions day after day. Their strategic position at the front of the mouth makes them absolutely essential for everyday functions, from taking the first bite of a meal, to assisting in the articulation of words, and contributing significantly to the expression of a smile. They are indeed the welcoming committee of our dental arch, constantly at work and playing a more multifaceted role than we often realize.

The Indispensable Front Guard

The strategic forward placement of incisors, while perfect for their cutting and aesthetic duties, also means they are often the first teeth to encounter external forces, whether from an accidental bump, a fall during childhood play, or a sports-related impact. Their relatively thin, blade-like structure, so effective for slicing through food, can make them more susceptible to chipping or fracture compared to the more robust, blocky molars if subjected to undue stress or trauma. This isn’t indicative of a design flaw, but rather a natural consequence of their specialized role and prominent, somewhat exposed location in the dental arch. They are built for precision cutting, not for brute force applications like cracking nutshells, tearing open packages, or biting fingernails – tasks best left to actual tools specifically designed for such purposes!

Recognizing their critical role and unique anatomical design helps us appreciate these often-overlooked dental heroes. They are not just passive structures fixed in our jaws; they are active, dynamic participants in our daily lives, facilitating nourishment, enabling clear communication, and shaping our social interactions through the power of a smile. Each time you effortlessly bite into a piece of fruit, clearly pronounce a word beginning with ‘t’ or ‘d’, or share a confident grin, your incisors are performing their duties with remarkable efficiency and elegance. Their sleek, effective design is a testament to the intricate and highly functional engineering found within the human body, a front line that serves us faithfully throughout our lives.