Our mouths are bustling communities of specialized workers, each tooth type playing a distinct role in the fascinating process of breaking down food. We often marvel at the sharp incisors at the front, perfect for snipping, or the mighty molars at the back, the heavy-duty grinders. Then there are the pointed canines, the fanged heroes of gripping and tearing. But nestled between these distinct specialists lie the often-overlooked premolars, a group of teeth that perform a crucial, transitional role. They are the vital link, the true bridges in our dental arch, ensuring that food makes a smooth and efficient journey from the initial tear to the final grind.

The Front-Line Specialist: The Canine

Before we can fully appreciate the premolar’s role, let’s consider its neighbor, the canine. Humans typically have four canine teeth, two in the upper jaw and two in the lower, situated at the corners of the dental arch. Their most striking feature is their single, pointed cusp. This design isn’t accidental; it’s perfectly engineered for their primary tasks: gripping and tearing food. Think of biting into a tough piece of meat or a crunchy apple; the canines are the first to engage in a serious way, puncturing and ripping with focused force. They are incredibly strong, with long roots that anchor them firmly in the jawbone, allowing them to withstand considerable pressure. However, while excellent at initiating the breakdown of tougher food items, canines aren’t designed for extensive chewing or grinding.

The Back-End Powerhouse: The Molar

At the other end of the functional spectrum, far back in the mouth, lie the molars. These are the largest and strongest teeth, built like miniature millstones. Adult humans typically have up to twelve molars (including wisdom teeth), and their broad, relatively flat surfaces are adorned with multiple cusps and grooves. This complex topography is ideal for their job: crushing and grinding food into smaller, digestible particles. Molars don’t tear; they pulverize. They take the larger pieces passed back by other teeth and systematically break them down, mixing them with saliva to begin the digestive process. Their multi-rooted structure provides a wide, stable base to handle the significant forces generated during powerful chewing.

Enter the Premolars: The Versatile Connectors

Now, imagine the journey of food. It’s been snipped by incisors and perhaps torn by canines. If it were passed directly to the broad, flat molars, the transition might be awkward. Large, roughly torn pieces might not be efficiently handled by the molars initially, and the canines certainly aren’t equipped to do any grinding. This is where the premolars, also known as bicuspids, step in. There are eight premolars in the adult dentition, two situated behind each canine and just in front of the molars. Their very position hints at their function: they are the intermediate processors, the crucial link that bridges the functional gap between the tearing action of the canines and the heavy grinding action of the molars.

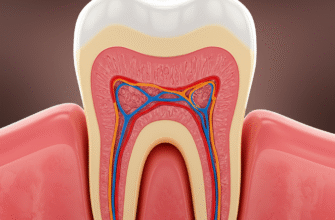

Anatomy of a Bridge-Builder: A Closer Look at Premolars

The design of premolars is a fascinating blend of canine and molar characteristics, perfectly suiting them for their transitional duties.

Location and Number

As mentioned, adults have eight premolars, four in the upper jaw (maxilla) and four in the lower jaw (mandible). They are numbered as first and second premolars, with the first premolar being closer to the canine and the second premolar closer to the first molar. This strategic placement is key to their role in the sequential processing of food.

Cusps: The Key to Versatility

The term “bicuspid” traditionally used for premolars means “two cusps.” Most premolars indeed have two prominent cusps: a buccal cusp (towards the cheek) and a lingual or palatal cusp (towards the tongue or palate). The buccal cusp is often sharper and more prominent, reminiscent of a canine’s point, allowing it to assist in piercing and tearing. The lingual cusp is typically more rounded and works in conjunction with the buccal cusp to begin the crushing and grinding process. This dual-cusp design is the hallmark of their adaptability.

However, there’s some variation. For instance, mandibular first premolars often have a large buccal cusp and a much smaller, sometimes non-functional, lingual cusp, making them appear more canine-like in some respects. Mandibular second premolars can be quite variable, sometimes presenting with three cusps (one buccal and two smaller lingual cusps), giving them a more molar-like appearance and function. These variations further underscore their role as adaptable, transitional teeth.

Premolars, often called bicuspids, typically possess at least two distinct cusps, though some lower second premolars may have three. This unique cusp anatomy is fundamental to their role in both grasping food, similar to canines, and beginning the grinding process, like molars. They effectively act as a preparatory stage, making the food more manageable before it reaches the powerful molars for final processing.

Roots: Anchoring the Transition

The root structure of premolars also reflects their intermediate nature. Most premolars, specifically the mandibular premolars and maxillary second premolars, usually have a single root, though it’s often more robust than an incisor root. However, maxillary first premolars are a common exception; they frequently have two roots (a buccal and a palatal root), or at least a single root that is deeply grooved, indicating a tendency towards bifurcation. This two-rooted anchorage in maxillary first premolars provides extra stability for the forces they encounter, especially as they are the first in line to receive food from the canines.

How Premolars Master the Middle Ground: Their Functional Significance

The true importance of premolars lies in their dynamic function, seamlessly connecting the actions of the teeth before and after them.

The Food Processing Relay

Imagine a piece of food, say a carrot stick. The incisors might bite off a piece. If it’s particularly fibrous, the canines might be engaged to tear it into a more manageable segment. At this point, the premolars take over. Their sharper buccal cusps can further pierce and hold the food, while the interplay between the buccal and lingual cusps begins to crush and break it down. They don’t just passively pass food along; they actively engage in reducing its size. This initial grinding is less powerful than that of the molars but is crucial. It prepares the food bolus, making it more uniform and easier for the molars to tackle. Without premolars, the molars would have a much tougher job, and the entire chewing process would be less efficient.

Bite Force Distribution and Occlusal Harmony

Premolars play a significant role in distributing chewing forces across the dental arch. When you chew, considerable pressure is exerted. If this force were concentrated only on the front or back teeth, it could lead to excessive wear or even damage. Premolars help to absorb and distribute these forces more evenly. They work in concert with their opposing teeth in the other jaw to ensure a balanced bite (occlusion). Their intermediate size and cusp design allow them to interlock effectively, contributing to the stability of the entire bite. This harmonious interaction is vital not just for chewing but for the long-term health of the jaw joints and other teeth.

Maintaining Arch Form and Aesthetics

Beyond their direct role in mastication, premolars contribute to the overall structure and aesthetics of the dental arch. They help maintain the proper spacing between canines and molars, preventing these teeth from drifting or tilting. This ensures that the arch maintains its correct U-shape. A full complement of teeth, including healthy premolars, supports the cheeks and lips, contributing to a fuller facial profile. While the “smile teeth” are often considered to be the incisors and canines, the premolars are visible in many smiles, providing a smooth visual transition from the pointed canines to the broader molars, thus contributing to a more harmonious and natural appearance.

Developmental Journey: From Primary Molars to Permanent Workhorses

An interesting aspect of premolars is their developmental path. Unlike incisors, canines, and molars which have primary (baby) predecessors that they largely resemble, permanent premolars actually replace primary molars. Children do not have premolars in their primary dentition. Instead, they have eight primary molars (two in each quadrant). As a child grows and their jaw develops, these primary molars make way for the permanent premolars. This transition typically occurs between the ages of 9 and 12. The emerging premolars are larger than the primary incisors or canines but generally smaller than the permanent molars they precede, fitting perfectly into their transitional space and role.

The Unsung Heroes: Why Premolars Deserve Our Attention

Because they are not as dramatically pointed as canines or as massively broad as molars, premolars can sometimes be overlooked. However, their role is far from minor. They are true workhorses, essential for efficient chewing and overall dental health. Like all teeth, premolars are susceptible to common dental issues. Their occlusal surfaces, with their cusps and grooves, can trap food particles and bacteria, making them prone to cavities if not cleaned properly. Regular brushing, flossing, and dental check-ups are just as important for premolars as for any other tooth.

Losing a premolar can have more significant consequences than one might think. It can disrupt the chewing process, placing extra strain on adjacent teeth. It can also lead to shifting of neighboring teeth, affecting the bite and potentially leading to other complications. Therefore, appreciating their function helps us understand the importance of caring for these vital connecting teeth.

In the complex machinery of our mouths, every part has a purpose. The premolars, with their unique blend of features, exemplify efficient design. They are not just space fillers; they are active, essential participants in the first stages of digestion. They ensure that the journey of food through the mouth is a well-coordinated relay, transforming what we eat into something our bodies can use. So, the next time you enjoy a meal, take a moment to appreciate the silent, efficient work of your premolars – the indispensable bridges in your bite.