The oral cavity, a gateway to both the digestive and respiratory systems, is lined by a remarkable and diverse tissue known as the oral epithelium. This lining, far from being a simple passive barrier, is a dynamic and specialized surface, constantly adapting to the various challenges it encounters. From the mechanical stresses of chewing to the subtle detection of flavors, the epithelium of the mouth plays a pivotal role. Understanding its different types is key to appreciating the intricate functionality of this vital anatomical region.

Broad Categories: A Functional Overview

Functionally, the oral epithelium can be broadly classified into three main categories, each tailored to the specific demands of the area it covers:

- Masticatory Mucosa: This is the tough guy of the oral lining. Found in areas subjected to significant friction and pressure during chewing, such as the gingiva (gums) and the hard palate.

- Lining Mucosa: This type offers flexibility and mobility. It covers the inner surfaces of the cheeks (buccal mucosa), lips (labial mucosa), the floor of the mouth, the underside of the tongue (ventral surface), the soft palate, and the alveolar mucosa, which covers the bone supporting the teeth.

- Specialized Mucosa: As the name suggests, this category is equipped for a unique function – taste sensation. It is found predominantly on the dorsal (upper) surface of the tongue, where it houses taste buds within various papillary structures.

Delving Deeper: Histological Classifications

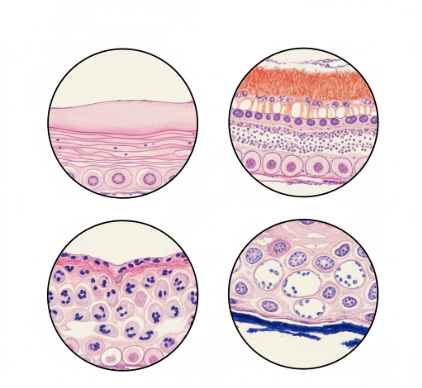

At a microscopic level, the vast majority of oral epithelium is classified as

stratified squamous epithelium. This means it is composed of multiple layers of cells, with the outermost cells being flattened (squamous). However, a crucial distinction within this classification is whether the epithelium is keratinized or non-keratinized, which significantly impacts its properties.

Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium

This type of epithelium is designed for protection against mechanical injury and abrasion. Keratin is a tough, fibrous protein that also makes up our skin, hair, and nails. In the oral cavity, keratinization provides a resilient surface. There are generally two recognized forms of keratinization in the oral mucosa:

- Orthokeratinized: This is considered complete keratinization. The outermost layer, the stratum corneum, is composed of dead cells densely packed with keratin, and these cells have lost their nuclei.

- Parakeratinized: This form is also protective but is considered an incomplete keratinization. The cells in the stratum corneum retain their nuclei, although these nuclei are often shrunken and condensed (pyknotic). Parakeratinization is very common in the gingiva.

The layers of keratinized epithelium, from deep to superficial, are typically:

- Stratum Basale (Basal Layer): The deepest layer, a single row of cuboidal or columnar cells that are actively dividing (mitotic). These cells are responsible for renewing the epithelium.

- Stratum Spinosum (Prickle Cell Layer): Several layers thick, composed of polyhedral cells. These cells are connected by numerous desmosomes (cell junctions), which appear as “prickles” or spines under a microscope when the cells shrink during tissue preparation.

- Stratum Granulosum (Granular Layer): Characterized by cells containing keratohyalin granules, which are precursors to keratin. This layer is more prominent in orthokeratinized epithelium.

- Stratum Corneum (Keratinized Layer): The outermost layer, composed of flattened, dead (in orthokeratinization) or dying (in parakeratinization) cells filled with keratin. This layer is continuously shed and replaced.

Non-keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium

Found in areas requiring greater flexibility and less subject to intense friction, non-keratinized epithelium lacks the tough, superficial layer of keratin found in its counterpart. It provides a moist, pliable lining.

The layers of non-keratinized epithelium, from deep to superficial, are:

- Stratum Basale (Basal Layer): Similar to that in keratinized epithelium, responsible for cell renewal.

- Stratum Intermedium (Intermediate Layer): Corresponds to the stratum spinosum but the cells are larger and flatter than those in the spinosum of keratinized tissue. They still have desmosomal connections.

- Stratum Superficiale (Superficial Layer): The outermost layer, composed of flattened, nucleated cells that are still viable. These cells are shed and replaced from below.

The oral epithelium is a highly dynamic tissue. It undergoes constant renewal, with cells migrating from the basal layer to the surface before being shed. This turnover rate varies depending on the specific region of the oral cavity and its functional demands, ensuring the integrity of this vital protective barrier.

A Tour of the Oral Cavity: Epithelium by Location

The Masticatory Mucosa Zones

Gingiva (Gums): The gingiva surrounds the teeth and covers the alveolar bone. It is predominantly

parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium, though areas of orthokeratinization can also be present. Its firm attachment to underlying bone and tooth makes it well-suited to withstand the forces of chewing.

Hard Palate: The roof of the mouth, specifically its anterior, bony portion, is covered by

orthokeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It is also firmly attached and features rugae (ridges) that aid in food manipulation.

The Lining Mucosa Regions

The lining mucosa is generally characterized by its

non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, offering suppleness and the ability to stretch.

Buccal Mucosa (Inner Cheeks): This lining is relatively thick and flexible, adapting to the movements of chewing and speaking.

Labial Mucosa (Inner Lips): Similar to the buccal mucosa, it is non-keratinized and pliable. It contains numerous minor salivary glands.

Alveolar Mucosa: Found apical to the attached gingiva, this mucosa is thin, loosely attached, and more reddish due to its rich blood supply being visible through the thinner epithelium. It allows for movement of the lips and cheeks.

Floor of the Mouth: This area is lined by a very thin non-keratinized epithelium. Its permeability is higher here than in other oral regions, a factor considered in sublingual drug administration.

Ventral Surface of the Tongue (Underside): Also covered by thin, non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, allowing for the tongue’s high degree of mobility.

Soft Palate: The posterior, fleshy part of the roof of the mouth. It is more mobile than the hard palate and is also lined by non-keratinized epithelium. It plays a role in swallowing and speech.

The Specialized Mucosa: The Dorsal Tongue

The upper surface of the tongue is unique, covered by specialized mucosa designed for both mechanical functions and taste perception. It features various types of papillae:

- Filiform Papillae: The most numerous, these are slender, conical projections that give the tongue its characteristic rough texture. They are covered by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium and primarily serve a mechanical role, aiding in gripping food. They do not contain taste buds.

- Fungiform Papillae: Mushroom-shaped projections, scattered among the filiform papillae, particularly noticeable near the tip and sides of the tongue. They are covered by a thinner, often lightly keratinized or non-keratinized epithelium and typically contain taste buds on their superior surface. They appear as red dots because their rich blood supply is visible.

- Circumvallate (Vallate) Papillae: Large, dome-shaped papillae, usually 8 to 12 in number, arranged in a V-shape at the back of the tongue. They are surrounded by a circular trough or sulcus. Their superior surface is often keratinized, but the epithelium lining the sides of the papillae within the trough is non-keratinized and rich in taste buds. Ducts of von Ebner’s serous glands open into these troughs, helping to cleanse them.

- Foliate Papillae: Found on the posterior lateral borders of the tongue as a series of vertical folds or ridges. Their epithelium is non-keratinized and contains numerous taste buds, especially in younger individuals.

A Special Case: Junctional Epithelium

While not fitting neatly into the broad categories, the

junctional epithelium (JE) deserves special mention. This is a unique band of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium that forms the attachment between the gingiva and the tooth surface at the base of the gingival sulcus or pocket. It is highly permeable and has a rapid turnover rate, playing a crucial role in sealing off the underlying periodontal tissues from the oral environment.

Cellular Residents of the Oral Epithelium

While keratinocytes are the principal cell type, forming the structural backbone of the epithelium, other non-keratinocyte cells reside within its layers, contributing to its overall function:

- Melanocytes: Located in the basal layer, these cells produce melanin pigment, contributing to mucosal coloration, particularly in individuals with darker skin.

- Langerhans Cells: These are dendritic cells found mainly in the suprabasal layers (above the basal layer). They are antigen-presenting cells, playing a role in the immune surveillance of the oral mucosa.

- Merkel Cells: Located in the basal layer, these cells are associated with nerve endings and are thought to function as touch receptors.

The intricate tapestry of epithelial types within the oral cavity reflects a sophisticated adaptation to diverse functional demands. From the robust, abrasion-resistant surfaces of the gums and hard palate to the delicate, taste-perceiving papillae of the tongue and the flexible lining of the cheeks, each epithelial variant contributes to the health and normal operation of the mouth. This complex lining not only protects underlying tissues but also facilitates essential processes like eating, speaking, and tasting, highlighting its importance as a first line of interaction with the external world.