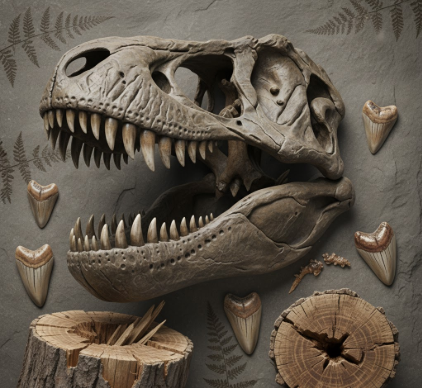

Imagine peering into the mouth of a creature that lived millions of years ago. What could its teeth tell us? When it comes to dinosaurs, their dental structures are a treasure trove of information, offering profound insights into their diets, behaviors, and the very ecosystems they inhabited. The fossils of these ancient giants, particularly their teeth and jawbones, whisper stories of a world vastly different from our own, a world where survival depended heavily on having the right kind of bite.

Unpacking the Prehistoric Smile: Clues in the Jaws

Teeth are remarkably resilient structures. Composed of hard enamel and dentine, they often fossilize exceptionally well, sometimes becoming the only surviving remnants of certain dinosaur species. Each tooth, whether a tiny serrated blade or a massive, banana-sized crusher, is a piece of a much larger puzzle. Paleontologists meticulously study their shape, size, wear patterns, and arrangement within the jaw to reconstruct the feeding habits of these long-extinct animals. Were they tearing flesh, grinding tough plants, or perhaps doing something entirely unexpected?

The jaw mechanics also play a crucial role. The way the upper and lower jaws articulated, the muscle attachment points, and the overall skull structure all contribute to understanding how a dinosaur processed its food. It’s not just about the teeth themselves, but how they functioned as part of a complex biological machine.

Herbivorous dinosaurs evolved an astonishing array of dental adaptations to cope with the diverse and often challenging plant life of the Mesozoic Era. From towering trees to fibrous ferns, their food sources demanded specialized equipment.

Hadrosaurs: The Grinding Machines

Duck-billed dinosaurs, or hadrosaurs, were masters of mastication. They possessed incredible dental batteries – hundreds, sometimes thousands, of teeth packed tightly together in their jaws, forming broad, uneven surfaces. As older teeth wore down from grinding coarse vegetation, new ones continuously erupted from below to replace them. This constant conveyor belt of teeth ensured they always had an efficient grinding mill to process leaves, twigs, and possibly even woody material. The complexity of these dental batteries is a testament to the evolutionary pressures of a plant-based diet.

Sauropods: Giants with Gentle Bites?

The colossal long-necked sauropods, like

Brachiosaurus and

Diplodocus, present a different picture. Their teeth were often simpler, peg-like or spoon-shaped, seemingly ill-suited for extensive chewing. It’s widely believed that these giants used their teeth more like rakes, stripping foliage from branches. The actual breakdown of this tough plant matter might have occurred further down the digestive tract, possibly aided by gastroliths – stomach stones – that helped grind food in a muscular gizzard, much like some modern birds. The sheer volume of food required to sustain such massive bodies meant efficient food gathering was key.

Ceratopsians: Shearing Power

Horned dinosaurs, such as the iconic

Triceratops, combined a powerful beak with sophisticated dental batteries. The sharp, horny beak at the front of their mouths was perfect for snipping off tough plants. Behind this beak, rows of teeth were arranged into shearing surfaces. As the ceratopsian closed its jaws, these teeth slid past each other like scissor blades, slicing vegetation into manageable pieces. This combination of beak and shearing teeth made them highly effective consumers of fibrous flora.

The Carnivore’s Arsenal

Predatory dinosaurs, the carnivores, evolved teeth designed for dispatching prey and processing meat. Their dental weaponry varied greatly, reflecting different hunting strategies and prey preferences.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Bone Crusher

The mighty

Tyrannosaurus Rex wasn’t just a biter; it was a bone-crusher. Its teeth were enormous, thick, and serrated, some reaching over six inches in length above the gum line. These weren’t delicate slicing tools but robust daggers capable of puncturing thick hides and shattering bone. Fossil evidence, including T. rex bite marks on other dinosaur bones and even coprolites (fossilized feces) containing bone fragments, confirms their powerful, bone-crunching bite. The sheer force generated by a T. rex jaw was immense, allowing it to inflict catastrophic damage.

Raptors: Precision Slicers

Smaller, agile predators like

Velociraptor and

Deinonychus, part of the dromaeosaurid family, had different dental tools. Their teeth were generally smaller, recurved (curved backward), and finely serrated, ideal for slicing through flesh. While their famous sickle claws on their feet did much of the killing work, their teeth played a crucial role in tearing apart their prey once subdued. These teeth were built for efficiency in flesh-tearing, not necessarily bone-crushing.

Spinosaurus: The Fish Hunter’s Grasp

The enigmatic

Spinosaurus, with its crocodile-like snout and conical teeth, offers a glimpse into a more specialized predatory niche. Unlike the blade-like teeth of many other theropods, Spinosaurus teeth were relatively straight, pointed, and lacked significant serrations. This type of dentition is excellent for gripping slippery prey, such as large fish, which are thought to have been a primary component of its diet. Its jaw structure and tooth morphology point towards an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle, a unique adaptation among large predatory dinosaurs.

A Lifetime Supply: The Miracle of Dinosaur Tooth Replacement

One of the most fascinating aspects of dinosaur dental biology is their ability to continuously replace their teeth. Unlike mammals, which typically get only two sets of teeth (baby and adult), most dinosaurs were polyphyodont, meaning they grew new teeth throughout their lives. This was a critical adaptation, especially for herbivores that subjected their teeth to immense wear and tear, and for carnivores whose teeth could be damaged or lost during hunting or feeding.

Fossil jaws frequently show teeth in various stages of eruption, with new crowns pushing out old, worn ones. Shed dinosaur teeth are also relatively common fossils, providing further evidence of this constant replacement cycle. The rate of replacement varied among different dinosaur groups, likely correlating with their diet and the stress placed on their teeth. For instance, hadrosaurs, with their intensive plant-grinding, probably replaced teeth quite rapidly.

Fossil evidence strongly indicates that most, if not all, dinosaurs possessed the remarkable ability to replace their teeth continuously throughout their lives. This polyphyodont condition meant they were never without a functional set of dentition, crucial for survival. The rate of replacement varied between species, adapting to their diet and tooth wear, ensuring an always-ready toolkit for feeding.

This continuous supply meant that a broken tooth wasn’t a catastrophe for a dinosaur; a new one was always on its way. It’s a feature shared with many modern reptiles, highlighting a long and successful evolutionary strategy.

When Teeth Went Wrong: Prehistoric Dental Woes

Despite the efficient replacement system, dinosaur teeth weren’t immune to problems. Paleontologists occasionally find evidence of dental pathologies. Extreme wear, beyond the normal scope, is sometimes visible, particularly in older individuals or those whose replacement system might have slowed. Broken teeth are common, especially among large carnivores whose powerful bites could result in damage if they hit something unexpectedly hard, even bone.

While infections and abscesses are harder to identify in the fossil record, some specimens do show signs of bone damage around tooth sockets that could indicate such issues. However, the constant shedding and replacement of teeth likely minimized the long-term impact of many dental problems that would cripple a mammal. If a tooth became infected or severely damaged, it would eventually be shed and replaced by a healthy successor. This natural mechanism provided a form of prehistoric dental care, albeit a passive one.

Beyond the Bite: Other Dietary Clues

While teeth are primary indicators, other fossils provide corroborating or additional information about dinosaur diets and feeding behaviors.

Coprolites: The Inside Scoop

Fossilized dung, or coprolites, can be incredibly revealing. When well-preserved, these trace fossils can contain undigested remnants of a dinosaur’s last meals. Plant fibers, seeds, pollen, and even bone fragments or fish scales found within coprolites offer direct evidence of what a particular dinosaur consumed, helping to confirm or refine dietary hypotheses based on tooth morphology.

Gastroliths: Nature’s Grinding Stones

As mentioned with sauropods, gastroliths – smooth, polished stones found in the abdominal region of some dinosaur skeletons – are thought to have been deliberately swallowed. These stones would have churned in a muscular gizzard, helping to break down tough plant material that the dinosaur’s teeth couldn’t fully process. The presence of gastroliths suggests a digestive strategy that compensated for less specialized chewing teeth.

Bite Marks: Stories Etched in Bone

Bite marks on fossilized bones tell vivid stories of predator-prey interactions and feeding behaviors. The shape and spacing of tooth marks can often be matched to a specific type of predatory dinosaur, revealing who was eating whom. Healed bite marks can also indicate survival from an attack or even non-lethal combat between rivals of the same species. These traces provide dynamic snapshots of life and death in the Mesozoic.

The Ever-Evolving Picture of Dinosaur Dining

The study of dinosaur dental habits is a dynamic field, constantly being updated by new fossil discoveries and analytical techniques. Microscopic wear analysis can reveal the precise movements of jaws and the types of food being processed. Isotopic analysis of tooth enamel can offer clues about an animal’s environment and diet. Each new fossil, each new study, adds another layer to our understanding of these magnificent creatures and how they interacted with their world through the fundamental act of eating.

What their fossils reveal is a stunning diversity of dental adaptations, from the sophisticated grinding batteries of herbivores to the formidable weaponry of carnivores. The prehistoric world was a tough place to make a living, and for dinosaurs, having the right set of teeth—and a constant supply of replacements—was often the difference between thriving and extinction. Their dental legacy, etched in stone, continues to fascinate and inform us about the intricate tapestry of life millions of years ago.