The lining of our oral cavity, that ever-busy gateway to our digestive and respiratory systems, is far more complex than a simple surface. It’s a multi-layered shield, a sensory organ, and a secretory surface all rolled into one. While the outermost epithelial layer and the immediately underlying lamina propria often get the spotlight, there’s a deeper, often less heralded, layer that plays an absolutely pivotal role in the function and resilience of the oral tissues: the submucosa. This layer isn’t uniformly present or structured throughout the mouth; its characteristics shift dramatically depending on the specific demands of each region.

Think of the oral mucosa as a sophisticated fabric. The epithelium is the visible, protective top weave. The lamina propria is the tight, supportive backing. And the submucosa? It’s the versatile underpadding, providing cushioning, flexibility, and vital supply lines. It is typically found nestled between the lamina propria and the deeper structures of the oral cavity, which could be muscle (as in the cheeks or lips) or bone (as in the hard palate or alveolar ridges).

Unpacking the Submucosa: Its Core Components

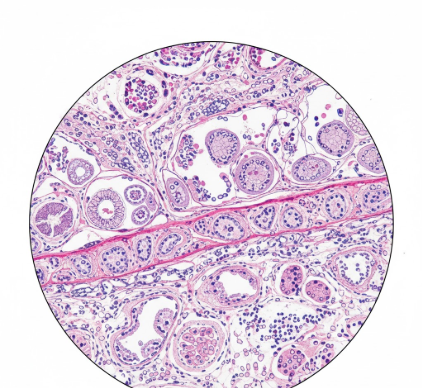

At its heart, the submucosa is a layer of

loose connective tissue. This “looseness” is key to many of its functions, allowing for a degree of movement and housing a variety of important structures. Unlike the denser lamina propria, the submucosa offers more space, making it an ideal conduit and reservoir.

Let’s delve into the common constituents that give the submucosa its functional capabilities:

Blood Vessels: A rich network of arteries, veins, and capillaries courses through the submucosa. Larger arterial branches enter this layer, subdividing into smaller arterioles that then ascend to supply the lamina propria and, indirectly, the avascular epithelium. Venules collect deoxygenated blood and waste products, merging into larger veins that exit the submucosa. This vascularity is crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients, removing waste, and facilitating rapid repair and immune responses. The density of these vessels can also influence the color of the oral mucosa.

Nerves: The submucosa is thoroughly innervated. It contains larger nerve bundles that branch out to provide sensory information – touch, pressure, pain, and temperature – to the overlying layers. These nerves are essential for protecting the oral cavity from harm and for functions like discerning food texture. Autonomic nerve fibers also travel within the submucosa, primarily to control the secretory activity of minor salivary glands and to regulate blood flow through vasodilation and vasoconstriction.

Lymphatic Vessels: Paralleling the blood vascular system, lymphatic capillaries and larger vessels form an extensive drainage network within the submucosa. These vessels are vital for collecting excess tissue fluid, proteins, and, importantly, for transporting immune cells and antigens to regional lymph nodes. This system plays a critical role in the oral cavity’s immune surveillance and defense mechanisms.

Glandular Elements: Many regions of the oral cavity are dotted with minor salivary glands, and the bodies of these glands (the acini) are frequently located within the submucosa. Their ducts then traverse the submucosa and lamina propria to open onto the epithelial surface, delivering saliva that aids in lubrication, initial digestion, and maintaining oral hygiene. The presence and density of these glands significantly influence the character of the submucosa in different locations.

Adipose Tissue: Clusters of fat cells, or adipose tissue, can be a prominent feature of the submucosa in certain areas, such as the cheeks and parts of the soft palate. This fatty tissue provides cushioning, helps to absorb mechanical forces, and can contribute to the overall contour and pliability of the tissue. It also serves as an energy reserve.

Fibroblasts, Collagen, and Elastic Fibers: As a connective tissue layer, the submucosa is rich in fibroblasts – the cells responsible for producing and maintaining the extracellular matrix. This matrix is composed primarily of collagen fibers, which provide tensile strength, and elastic fibers, which impart recoil and flexibility. The relative amounts and arrangement of these fibers dictate the mechanical properties of the submucosa, such as its firmness or distensibility.

The submucosa acts as a crucial interface, transmitting vital supplies like blood and nerve signals from deeper body systems to the more superficial oral lining. Its composition varies significantly, tailoring its properties to the functional needs of each specific oral region. This adaptability is a hallmark of its design.

Regional Variations: A Tale of Adaptation

The oral cavity is not a homogenous environment. Different areas perform distinct functions, and the submucosa reflects this specialization perfectly. The presence, thickness, and composition of the submucosa are key differentiating features between the main types of oral mucosa: masticatory, lining, and specialized.

The Firmness of Masticatory Mucosa

Masticatory mucosa is found in areas subjected to high compressive and shear forces during chewing, namely the

gingiva (gums) and the

hard palate. Here, the submucosa’s character is all about providing a firm, resilient base.

In the gingiva, particularly the attached gingiva, the submucosa is often described as being

absent or very thin and dense. The lamina propria in these regions tends to blend almost directly with the periosteum (the connective tissue covering of bone). This arrangement, sometimes termed a

mucoperiosteum, results in a tight, immovable attachment of the mucosa to the underlying alveolar bone. This secure binding is essential to withstand the forces of mastication without the tissue stripping away from the teeth or bone.

Similarly, over much of the hard palate, especially in the midline raphe and the rugae (ridges), the submucosa is also relatively thin and firmly attached to the palatal bone. However, in the anterolateral and posterolateral zones of the hard palate, a more discernible submucosa is present, containing adipose tissue anteriorly (the “fatty zone”) and abundant minor salivary glands posteriorly (the “glandular zone”). Even here, though, the attachment to bone remains quite firm through dense bands of collagen.

The Flexibility of Lining Mucosa

Lining mucosa covers the vast majority of the oral cavity surfaces that require mobility and distensibility. This includes the

inner cheeks (buccal mucosa),

lips (labial mucosa),

soft palate,

floor of the mouth, and the

ventral (underside) surface of the tongue.

In these regions, the submucosa is generally

well-developed, thicker, and looser than in masticatory areas. This characteristic is vital for accommodating the movements associated with speech, chewing, and swallowing. The submucosa of the lining mucosa typically contains:

- Abundant elastic fibers: These allow the tissue to stretch and recoil, preventing tearing during functional movements.

- Numerous minor salivary glands: Especially prominent in the labial, buccal, and palatal regions, contributing to oral lubrication.

- Blood vessels and nerves: A rich supply, as seen elsewhere, but often with larger caliber vessels and more extensive branching to support the greater tissue mass and metabolic activity.

- Adipose tissue: Particularly in the cheeks, contributing to their fullness and cushioning properties.

The attachment to underlying muscle (in cheeks, lips, soft palate, tongue) or loosely to bone (floor of mouth) is facilitated by this flexible submucosal layer, allowing the overlying mucosa to glide and adapt.

Submucosa and Specialized Mucosa

The specialized mucosa of the

dorsal (top) surface of the tongue presents a unique situation. This surface is characterized by various types of papillae (filiform, fungiform, circumvallate, foliate), which are associated with taste and mechanical functions. The submucosa here is less distinctly defined as a separate layer compared to lining mucosa. The lamina propria of the dorsal tongue is very tightly bound to the underlying intrinsic muscle of the tongue. Minor salivary glands (glands of von Ebner, associated with circumvallate papillae, and posterior lingual mucous glands) have their bodies situated deep among the muscle fibers, effectively within what might be considered a modified submucosal environment, with their ducts opening into the troughs of papillae or onto the surface.

The Submucosa’s Crucial Roles

From the preceding descriptions, it’s clear that the submucosa is far from being a passive packing material. Its functions are diverse and essential for the health and operation of the oral cavity.

Support and Attachment: It provides mechanical support to the overlying epithelium and lamina propria. Critically, it dictates how these layers attach to deeper structures – firmly in masticatory areas for stability, or loosely in lining areas for mobility.

Nutritional and Sensory Conduit: The submucosa is the highway for blood vessels that nourish the avascular epithelium and the cellular components of the lamina propria and submucosa itself. It also carries the nerves that provide sensory feedback and autonomic control.

Glandular Function: By housing minor salivary glands, the submucosa plays a direct role in secreting saliva, which is indispensable for lubrication, buffering pH, initiating digestion, and antimicrobial action.

Mobility and Flexibility: The presence of elastic fibers and a looser connective tissue arrangement in the submucosa of lining mucosa permits the stretching and movement necessary for complex oral functions like speech and mastication. Adipose tissue within the submucosa contributes to cushioning and shaping.

Defense and Repair: The rich vascular and lymphatic networks within the submucosa are integral to the oral immune system. They facilitate the rapid deployment of immune cells to sites of injury or infection and help in clearing debris and pathogens. The fibroblasts and vascular supply are also key to wound healing and tissue repair processes.

A Layer of Dynamic Importance

The submucosa is a dynamic and regionally specialized layer, intricately involved in nearly every aspect of oral function. Its structural integrity and the health of its components are vital for maintaining a healthy oral environment. Understanding its basic anatomy reveals a sophisticated design tailored to meet diverse mechanical and physiological demands, highlighting its significance as more than just a “sub-layer,” but as a cornerstone of oral tissue architecture.

It’s important to remember that the submucosa’s structure is not static; it can change in response to various stimuli, age, and functional demands. The density of collagen, the amount of adipose tissue, and the activity of glands can all vary. This adaptability underscores its active role in oral physiology.

In essence, while the epithelium faces the oral environment directly, the submucosa works diligently behind the scenes, ensuring the entire mucosal system is well-supported, nourished, innervated, and capable of performing its myriad tasks. Its often-overlooked contributions are fundamental to the resilience and functionality of our oral cavity, making it a truly essential anatomical player.