Cementum, often an unsung hero in the oral cavity, plays a pivotal role in the health and stability of our teeth. This specialized, calcified connective tissue forms a thin layer covering the anatomical root of a tooth. Think of it as the crucial interface between the tooth root and the periodontal ligament, the supportive structure that anchors the tooth within its bony socket. While it shares some characteristics with bone, cementum is unique in its avascular nature – meaning it lacks its own blood supply – and its continuous, albeit slow, deposition throughout life. Understanding its different forms is key to appreciating its complex functions.

Delving into Acellular Cementum: The Primary Foundation

Often referred to as primary cementum,

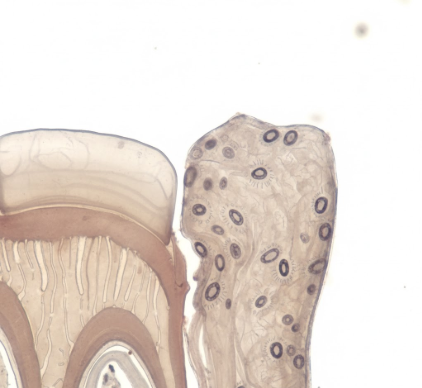

acellular cementum is the first type to be laid down, forming before the tooth even makes its grand entrance into the oral cavity during eruption. Its name gives a significant clue: “acellular” means it is devoid of the cells that produce it (cementoblasts) becoming entrapped within its matrix. Once these cementoblasts have completed their task of secreting the matrix, they typically remain on the surface, ready for potential future activity, rather than becoming embedded within the hardened tissue itself.

You’ll primarily find this type of cementum blanketing the cervical third to the coronal half of the tooth root, essentially the upper regions closer to the crown. Its formation is a relatively slow and meticulous process. The resulting tissue is densely packed and highly mineralized, providing a robust and stable surface. A critical feature of acellular cementum is its intimate involvement with Sharpey’s fibers. These are the terminal ends of the principal fibers of the periodontal ligament, which embed themselves like tiny anchors directly into the cementum on one side and the alveolar bone on the other. This connection is fundamental for tooth anchorage, transmitting occlusal forces and allowing for slight physiological tooth movement without damage.

The primary functions of acellular cementum revolve around this anchorage. It provides a firm attachment for the periodontal ligament fibers, ensuring the tooth remains securely in its socket. It also acts as a protective covering for the underlying dentin of the root, shielding it from resorption or other potential insults. Its dense, highly calcified nature makes it well-suited for these roles.

Exploring Cellular Cementum: The Adaptive Layer

In contrast to its acellular counterpart,

cellular cementum, also known as secondary cementum, typically begins its formation after the tooth has erupted and is in functional occlusion. As its name suggests, this type is characterized by the presence of cells, called cementocytes, which are entrapped within the cementum matrix. These cementocytes are essentially cementoblasts that have become embedded as the cementum was deposited around them. They reside in small spaces called lacunae and have cytoplasmic processes extending through tiny channels called canaliculi, allowing for some communication and nutrient exchange, albeit limited due to cementum’s avascularity.

Cellular cementum is predominantly found in the apical third (the tip) and interradicular areas (between roots in multi-rooted teeth) of the root. Its formation is generally more rapid and less uniform than that of acellular cementum. This faster deposition often results in a less mineralized and more irregularly arranged tissue compared to the primary type. While Sharpey’s fibers also embed into cellular cementum, they may be less regularly organized or less numerous in certain regions compared to their arrangement in acellular cementum.

The functions of cellular cementum are largely adaptive and reparative. It plays a significant role in maintaining tooth attachment in response to wear and tear. For instance, as enamel on the occlusal (chewing) surfaces wears down over time, cellular cementum can be deposited at the root apex to compensate for the loss of tooth length, helping to maintain the tooth’s occlusal relationship. It is also crucial in the repair of root fractures or areas of root resorption, filling in defects and attempting to restore the integrity of the root surface. This adaptability makes it vital for the long-term maintenance of tooth function.

Distinguishing Features and Interplay

The distinction between acellular and cellular cementum hinges on several key characteristics. The most obvious, of course, is the

presence or absence of embedded cementocytes. Acellular cementum is cell-free within its matrix, while cellular cementum houses these cells.

Their

timing and rate of formation also differ significantly. Acellular cementum forms first, slowly and pre-eruptively, establishing the initial root surface. Cellular cementum forms later, post-eruptively, often at a faster pace and in response to functional demands or the need for repair.

Location is another distinguishing factor: acellular cementum typically covers the coronal two-thirds of the root, whereas cellular cementum is more prevalent on the apical third and in furcation areas. This distribution reflects their primary roles – acellular for initial, stable anchorage, and cellular for later adaptation and repair at the root tip or in complex root anatomies.

Furthermore, there’s a difference in their

structural organization and mineralization. Acellular cementum tends to be more highly mineralized and regularly lamellated. Cellular cementum is generally less mineralized, and its structure can be more irregular, reflecting its more rapid and sometimes reactive deposition.

Cementum is a dynamic tissue, with acellular cementum primarily providing strong anchorage and cellular cementum offering adaptive and reparative capabilities. Both types contain Sharpey’s fibers for periodontal ligament attachment. Understanding these distinctions is fundamental to appreciating overall tooth support and maintenance mechanisms.

It’s important to note that these two types are not always sharply demarcated. There can be areas where they overlap, or one type may be deposited over the other. For example, layers of cellular cementum can be deposited over existing acellular cementum, especially in response to changing functional loads or reparative needs. This layering contributes to the incremental growth pattern of cementum throughout life.

The Broader Significance in Tooth Biology

The existence of these two distinct types of cementum underscores the sophisticated biological engineering involved in maintaining our dentition. Acellular cementum provides the steadfast, initial attachment that allows teeth to withstand the considerable forces of mastication from the moment they become functional. Its slow, organized formation creates a highly reliable interface for the periodontal ligament.

Cellular cementum, on the other hand, endows the tooth with a remarkable capacity for adaptation and self-preservation. Life isn’t static, and neither are the forces experienced by teeth. Changes in biting patterns, gradual tooth wear, or minor injuries to the root surface necessitate a responsive tissue. Cellular cementum fulfills this need by actively participating in processes that can compensate for lost tooth structure at the apex or attempt to mend areas of damage. The presence of cementocytes, even with their limited metabolic activity due to the avascular environment, allows this tissue to react to local stimuli.

This dual system ensures that teeth are not only well-anchored but can also respond to the ongoing demands and minor traumas encountered throughout an individual’s life. The continuous, albeit generally slow, deposition of cementum, particularly the cellular type, is a testament to the dynamic nature of the tooth’s supporting apparatus. It highlights how biological tissues can be both strong and adaptable, performing crucial roles in maintaining oral function.

Concluding Thoughts on Cementum’s Dual Nature

In summary, the acellular and cellular forms of cementum, while both contributing to the overall integrity and function of the tooth, possess distinct characteristics and fulfill specialized roles. Acellular cementum lays the primary groundwork for robust tooth anchorage, forming a highly mineralized and stable layer before the tooth even erupts. Cellular cementum, with its embedded cementocytes, offers a dynamic capacity for adaptation, repair, and compensation, forming predominantly after eruption and in response to functional stimuli.

Together, these two types of cementum ensure that our teeth are not only securely held within their sockets but can also respond to the physiological changes and challenges they encounter over a lifetime. Their collaborative effort is essential for maintaining the attachment apparatus, protecting the underlying dentin, and contributing to the longevity of the dentition. Understanding these nuanced differences provides a deeper appreciation for the complex biological systems that support our oral health and function. The intricate design of cementum, in its acellular and cellular expressions, is a perfect example of how structure dictates function in biological tissues.