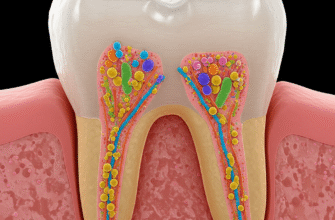

Nestled at the neck of every tooth, a critical boundary line marks the transition from the crown to the root. This landmark, known as the Cemento-Enamel Junction (CEJ), or sometimes the cervical line, is far more than just a simple demarcation. It represents a complex anatomical interface where two distinct hard tissues of the tooth – the enamel covering the crown and the cementum covering the root – come together. Understanding the intricacies of the CEJ is fundamental not only for appreciating tooth biology but also for various aspects of dental science and practice.

The Meeting Point: Enamel and Cementum Defined

To truly grasp the nature of the CEJ, we must first briefly acquaint ourselves with the two principal tissues that form this junction. Each possesses unique characteristics and plays a vital role in the tooth’s overall structure and function.

Enamel: The Crown’s Guardian

Enamel stands as the hardest substance in the human body, forming the resilient outer layer of the anatomical crown. Primarily composed of hydroxyapatite crystals meticulously arranged into rods or prisms, enamel provides the tooth with its wear resistance and the ability to withstand the formidable forces of mastication. It is a non-vital tissue, meaning it has no living cells, blood vessels, or nerves, and therefore cannot repair itself if damaged. At its cervical margin, where it approaches the root, the enamel thins out, tapering to meet the cementum at the CEJ.

Cementum: The Root’s Anchor

Covering the root of the tooth is cementum, a specialized calcified connective tissue. While also hard, cementum is softer than enamel and dentin. Its primary role is to provide attachment for the periodontal ligament fibers, which anchor the tooth to the alveolar bone socket. Unlike enamel, cementum is a vital tissue, capable of some repair and continuous deposition throughout life, particularly at the root apex. It is produced by cells called cementoblasts. The coronal-most extent of cementum is where it interfaces with enamel to form the CEJ.

Unveiling the Junctional Landscape: Types of CEJ Configurations

The relationship between enamel and cementum at the CEJ isn’t uniform across all teeth, or even around the circumference of a single tooth. Instead, several distinct patterns of this junction have been identified, each with its own anatomical presentation. These variations are crucial to understand, as they can influence the tooth’s response to external factors and are relevant in clinical contexts.

Three primary configurations describe how enamel and cementum meet or interact at the cervical line:

- Cementum Overlapping Enamel: This is the most frequently observed pattern. In this arrangement, the cementum extends slightly coronally to overlap the cervical edge of the enamel for a short distance. Imagine a thin layer of cementum gently draped over the terminal end of the enamel. This overlap provides a sealed junction, protecting the underlying dentin.

- Edge-to-Edge or Butt Joint: The second most common type features the enamel and cementum meeting at a distinct, sharp line, without any overlap. They abut each other directly, forming a flush surface. While this also forms a sealed junction, the direct meeting point might be considered slightly less protective than an overlap under certain stress conditions.

- The Gap or Failed Meeting: In a smaller percentage of cases, the enamel and cementum fail to meet at all. This results in a small gap or zone where the underlying dentin is exposed to the oral environment. This exposed dentin can be a site of sensitivity because dentin contains microscopic tubules that communicate with the tooth’s pulp.

It’s important to note that these configurations can vary not only from one tooth to another in the same individual but also on different surfaces (e.g., buccal vs. lingual) of the same tooth. A tooth might exhibit an overlap on one side and an edge-to-edge relationship on another.

A Closer Look: Microscopic Features and Development

Delving into the microscopic realm, the CEJ reveals further complexities. The interface itself is not always a perfectly smooth, geometrically defined line. Depending on the type of junction and the specific location, it can appear scalloped or irregular at high magnification. The nature of the crystalline structure of enamel and the more organic matrix-rich cementum means their union is a fascinating blend of mineralized tissues.

The formation of the CEJ is an intricate part of tooth development, or odontogenesis. During root formation, a structure called Hertwig’s Epithelial Root Sheath (HERS) plays a pivotal role. HERS guides the shape of the root and induces the differentiation of odontoblasts, which form root dentin. As HERS fragments and disintegrates near the future cervical line, mesenchymal cells from the dental follicle come into contact with the newly formed dentin and differentiate into cementoblasts. These cementoblasts then begin to deposit cementum, starting coronally and progressing apically. The precise signaling and timing of HERS breakdown and cementoblast activity are critical in determining which type of CEJ configuration will form. If cementogenesis begins slightly before enamel formation is fully complete at the cervical margin, an overlap might occur. If they conclude simultaneously, an edge-to-edge junction is likely. A slight delay or disruption in cementogenesis relative to enamel termination can lead to a gap.

Verified Anatomical Data: Studies consistently show specific prevalence rates for CEJ configurations. Generally, cementum overlapping enamel is found in approximately 60-65% of cases. An edge-to-edge relationship occurs in about 30% of instances, while a gap exposing dentin is the least common, appearing in roughly 5-10% of CEJ observations. These percentages can vary slightly depending on the population studied and the tooth type.

Why the CEJ Matters: Its Broader Significance

The Cemento-Enamel Junction is more than just an academic point of interest for anatomists; it holds considerable practical significance. For dental professionals, the CEJ is a critical anatomical landmark. It’s used to assess periodontal health, specifically when measuring periodontal pocket depths and clinical attachment loss. The position of the gingival margin relative to the CEJ is a key indicator of gum recession or inflammation.

Furthermore, the CEJ often dictates the cervical margin of dental restorations. When placing fillings or crowns, dentists aim to create a smooth, well-adapted margin, ideally at or near the CEJ, to prevent plaque accumulation and secondary decay. The type of CEJ present can influence how a restorative material bonds or adapts to the tooth structure in this sensitive area.

The integrity of the CEJ is also important in understanding the development of non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs), such as abrasion, erosion, and abfraction. These lesions often occur at the cervical region of the tooth, and the structural characteristics of the CEJ, including the thinness of enamel and the potential for exposed dentin in gap junctions, can make this area more susceptible to wear and damage over time. While the CEJ itself doesn’t cause these lesions, its anatomical nature is a contributing factor to their common location.

From a broader biological perspective, the precise formation and maintenance of this junction underscore the intricate coordination of developmental processes that lead to a functional tooth. Any disruption in these processes can lead to variations that, while often subclinical, highlight the complexity of this seemingly simple boundary.

In conclusion, the Cemento-Enamel Junction is a dynamic and variable anatomical feature that plays a crucial role in tooth structure, function, and health. From its diverse configurations at the meeting point of enamel and cementum to its importance as a clinical landmark, the CEJ is a testament to the sophisticated design of dental tissues. A thorough understanding of its anatomy provides valuable insights into the biological processes of the oral cavity and the principles guiding dental care.